“It’s happening, and it will transform your operations and strategy”. In 2015, a Harvard Business Review article made that very prediction about industrial 3D printing: the process of creating a physical object from a 3D digital model. In the article, which was called “The 3-D Printing Revolution”, author Richard D’Aveni argued that society had reached the “tipping point” for 3D printing, which was first discovered over 20 years prior. The first patent for an industrial 3D printing process called stereolithography (SLA) was filed in 1984, and within the next four years, scientists had also discovered another application of 3D printing – bioprinting – which pushed this technology into healthcare.

“It’s happening”

Bioprinting, also known as 3D bioprinting, uses cells, growth factors (naturally occurring substances that help cells proliferate) and biomaterials (like heart valves, artificial joints, and dental implants that are artificial but interact with the body’s natural components) to create structures that are realistic and personalized. Since a subject’s own cells can be used to create the 3D printed structure, the resulting model can represent any idiosyncrasies the subject has, including those at the cellular level. The printed structure is also living, able to act and react to its environment just as blood vessels, bone, organs, and tissues do within the body.

Bioprinting can also be faster, cheaper, and less invasive than current care options. For example, badly burned patients may require a skin graft: a process in which healthy skin from one part of their body is removed and used to replace the burned skin. With bioprinting, skin cells can potentially be printed directly onto a burn wound, conceivably eliminating the need for (sometimes multiple) skin graft surgeries and reducing treatment costs (which can range from $10.58 to over $125,000 per patient) as well.

“It will transform your operations and strategy”

Another medical field in which bioprinting can have a major impact is cancer. Since the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in 1938, novel treatments for oncology – and for many other medical conditions – must first be tested on animals before being tested in humans. Over the last 85 years, tests on dogs, guinea pigs, mice, monkeys, and more have been behind various health advancements, including in Alzheimer’s, cystic fibrosis, HIV, organ transplants, Parkinson’s, and polio as well as cancer.

As a 2014 article states, “Animal models have been essential in cancer research”. However, that same article argues that “animal models are limited in their ability to mimic the extremely complex process of human carcinogenesis [the formation of cancer], physiology and progression” and notes that the average rate of successful translation from animal models to clinical cancer trials is less than 8%. When animal-tested drugs are moved to human subjects, thus, those treatments may not work or could even cause additional harm. In those cases, the animal test subjects, of which there are estimated to be between 50 million and 115 million annually, may have to suffer for little benefit.

The usefulness of and ethical questions around using animal test subjects led to the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which was signed into law at the end of 2022. This Act allows animal testing to be replaced with certain other testing systems, such as cell-based assays (which use isolated cells to test the drug’s response), organ chips and micro-physiological systems (which recreate the functionality of organs in vitro), computer modeling, and “other non-human or human biology-based test methods”: a category that includes bioprinting.

The “tipping point”

As Ishani Malhotra, Founder and CEO of Carcinotech noted, her bioprinting startup has seen an increased response to its technologies and its capabilities since the passage of the FDA Modernization Act 2.0. Carcinotech, which takes its name from the Latin word “carcino” meaning “cancer”, manufactures 3D printed living tumors.

Prior to founding Carcinotech and while pursuing her Masters in Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Ms. Malhotra asked surgeons and oncologists to understand what they thought was the exact problem and market need in cancer therapeutics. The consensus, in her words, was “better testing models”, which could, in turn, lead to “more accuracy and better results”. Currently, it can take 10 to 15 years for an oncology drug to become commercially available, and the median cost of developing a cancer drug, according to a 2017 article, was $648 million (equivalent to over $794 million in 2023). If a drug is unsuccessful – a reality for about 97% to 98% of novel oncology drugs – that time and money are sunk costs.

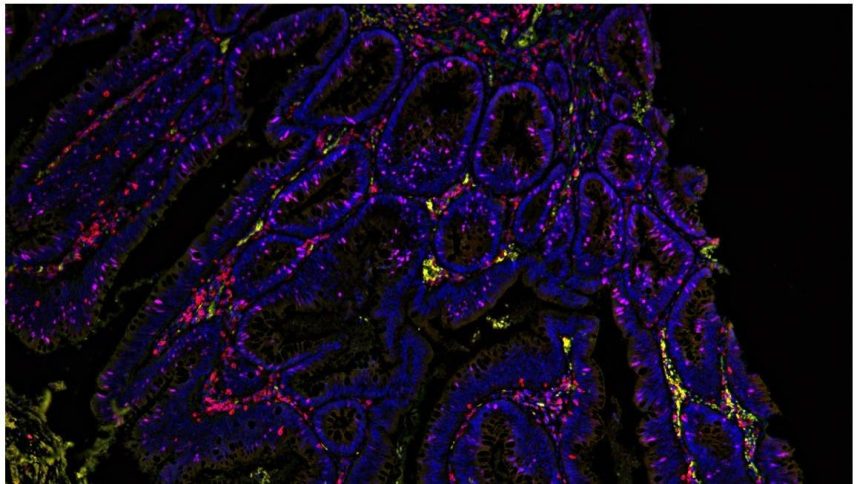

Carcinotech helps provide those “better testing models” to improve accuracy and time and financial investments. The company uses a cancer patient’s biopsy (an extraction of the patient’s cells or tissues) and blood to print 3D models of tumors for brain, breast, colorectal, lung, and ovarian cancers – and these cancers’ various subtypes. (Breast cancer, for example, has four main subtypes.) The company only recently added tumors for breast and ovarian cancers – the second and fifth most common causes of cancer death in women respectively – to its offerings: what Ms. Malhotra calls a “great achievement” since the fattiness of the tissue in these two cancers can make it challenging to collect enough cells to print a 3D tumor model.

Different oncology treatments can be tested on these living printed tumors, across cancer types and subtypes, by Carcinotech’s in-house team or by external pharmaceutical companies or CROs, for pre-clinical and drug testing. These printed micro-tumors can also be used to recommend the best course of action for the patients based on the way the printed tumors react to each treatment. One type of brain cancer, for instance, has a specific mutation that makes chemotherapy ineffective. Oncologists, though, may not check for that mutation and prescribe chemotherapy anyway: an unnecessary tax on the patient’s body, wallet, and hope for a remission. By showing that mutation from the onset, Carcinotech’s printed tumors help recommend a personalized treatment option, such as a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the cases of these brain cancer patients, to elicit a positive response. Since Carcinotech can print 96 tumors in 10 minutes, it can reach these conclusions and prescribe the best treatment relatively quickly.

The “revolution”

Carcinotech was founded in 2018: about 30 years after bioprinting was first discovered and three years after author Richard D’Aveni believed 3D printing was about to “go mainstream in a big way”. While Mr. D’Aveni was focused specifically on 3D industrial printing, its healthcare-focused cousin, bioprinting, may also be part of what he called the “3-D Printing Revolution”; companies like Carcinotech are using bioprinting to revolutionize and democratize cancer treatment options, making them cheaper and faster, more personalized and efficient, and more patient-friendly and less invasive than before. As new cancer cases are predicted to reach around 26 million by 2030 and cancer treatment costs continue to rise, the potential of bioprinting tumors can help offer cancer patients, now and in the future, a revolution(ary treatment) of their very own.

Read the full article here