Though Beijing would never use the word, it has effectively admitted failure. Today’s implicit confession is really the second of its kind in the past six months. The first one came at the start of the year when Beijing rescinded the lockdowns and quarantines that were the signal parts of its zero-Covid campaign. Party leadership had hoped that freeing people up to travel and spend would jumpstart China’s moribund economy. Even amid such hopes, the country’s leadership set itself a low 5% real growth target for 2023, far below pre-Covid growth averages. For a brief while, consumer spending took off, and, even though signs of weakness lurked behind the headlines, it looked as though the new policies would work. But now that economic weaknesses have become more apparent, Beijing has had to roll out a new stimulus package and in doing so effectively admit that the original policy (to correct for the old, failed Covid policy) also had failed.

The authorities in the Forbidden City have instructed the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to cut its benchmark interest rates yet again, presumably to increase borrowing and lending among consumers and to encourage investment by private businesses. Beijing has already had to channel funds to the failed property development sector, but still faces little response from an area that once amounted to fully 30% of the economy. Beijing has also turned to its tried-and-true stimulus of launching massive infrastructure projects.

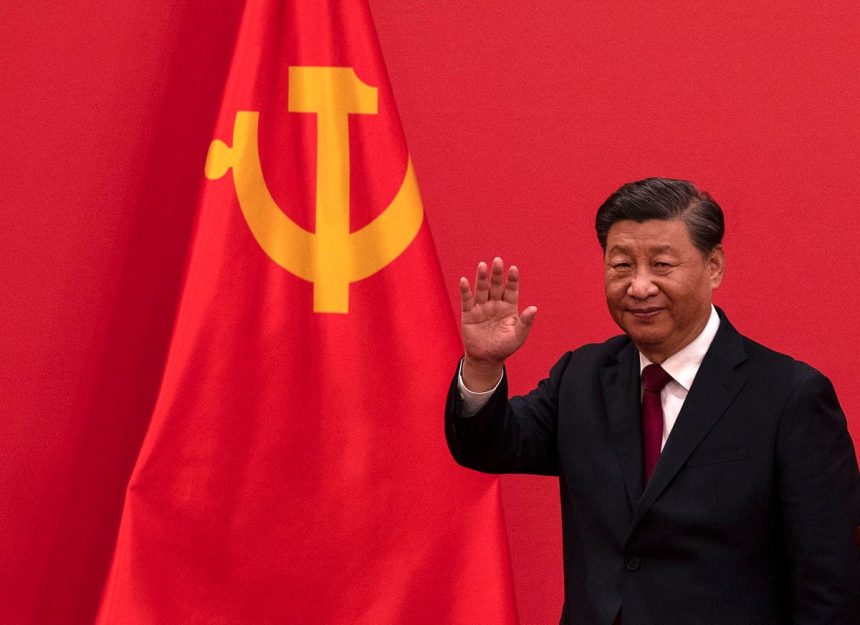

Taking these steps must have been hard for President Xi Jinping and the party leadership. All run counter to many statements made over the course of the last few years. Early in 2022, Xi decried private business for failing to follow party dictates as avidly as he would like. Now, in recognition of thee need for private investment spending, he refers to such business owners as “one of us” and provides low interest rates as an incentive for them to invest. He and the party had previously criticized the speculative nature of the property sector and implemented policies to stop such activity — policies that no doubt contributed to the failure of many such development firms, Evergrande prominent among them. Now this latest stimulus package includes loosening of rules to allow people to buy more than one residence, in other words, speculate.

If going back on all these past positions were not difficult enough for the party leadership, Beijing has also had to admit the failures of past infrastructure spending, though as always not in so many words. In the past, local and provincial governments have had to finance most of Beijing’s grand projects. But so many of these failed to pay adequate returns that now many of these provincial and local governments are facing difficulty servicing their debts. In tacit admission of this past failure, Beijing for this new round of infrastructure spending has decided to rely on central government financing and to that end is issuing some 1 trillion yuan ($140 billion) in special treasury bonds.

Even so, it is far from apparent that Beijing’s latest effort will bear fruit, at least not enough to get the growth that the government wants. Chinese consumers have lost confidence in the future and seem more eager to save than to spend. It is now apparent that the consumer spending surge earlier this year was entirely the product of wealthier Chinese taking advantage of the new freedom after Covid lockdowns. With confidence shaken, most mid- and low-income Chinese remained reluctant to spend. The loss of consumer confidence is even more acute when it comes to real estate. However much Beijing now wants to see speculative spending, the past drop in real estate values – 11.8% over the last twelve months – is likely a more significant consideration to the average Chinese than a change in regulations. Meanwhile, private business remains wary and has hardly increased it investment spending at all – only 0.8% in the last year.

Such a policy scramble smells of desperation. The existence of these extraordinary measures revel how little is the likelihood that China’s economy will make the 5% real growth targeted for 2023. A shortfall in Chinese growth is certainly the view of the forecasting community. Ting Lu, chief China economist for Nomura, has compared China today to Japan in the 1990s, when weakened confidence after a real estate collapse set the country up for decades of weak growth and decline. He forecasts less than 4% real growth for China next year. Keyu Jin, associate professor at the London School of Economics, sums up matters by concluding that after last year’s round of infrastructure spending failed to get a response, Beijing has few options these days beyond throwing money at more big-ticket projects. Success will require more effort – and much more imagination – than Beijing has shown thus far.

Read the full article here