It was 1975, and Peter Cancro was 17 and in love. The object of his affection was a small mom-and-pop deli in the beach town of Point Pleasant, New Jersey, called Mike’s Subs.

Peter had worked there since he was 14 — at first wrapping subs, then waiting for the day he’d earn the right to slice meats. “Only certain people would slice,” he recalls, “because that was, like, where you had to really nail it.” Alongside his colleague buddies, he was always talking to the tourists who flocked to the ocean. There’s no way to know for sure, but Cancro thinks the deli had to be the highest-volume sub shop in the country, even back then. On an average summer day it went through “850 giant loaves a day,” Cancro says, “or $130,000 in sales a week, in today’s dollars.” He was always serving people, always memorizing their orders. Always tracking the details.

Then one night, Cancro heard from his mother that the shop’s owners were planning to sell. What happened next is a story Cancro has long relished telling. His mother asked him, “Why don’t you buy it?” With that question in his head, he started heading upstairs to bed. By the time he got to the top of the stairs, he thought, Why not me?

Related: Continued Expansion and Fair Wages Help Jersey Mike’s Stay a Cut Above the Competition

Cancro was still in high school (and planning to attend The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with notions of becoming a lawyer), but he skipped classes to research the financials and look for backers. Desperate, one Sunday after 9 p.m., he knocked on the door of his former football coach — who was, helpfully, also a banker — and asked for a loan to meet the brothers’ $125,000 asking price. The coach said yes. The deal went through. Peter Cancro became the owner of a mom-and-pop deli, while still living with his mom.

This is the origin story of Jersey Mike’s Subs, told and retold in media and marketing. Often, the story quickly flashes forward to the present day — where Cancro’s little store is now a franchising behemoth. How big? Big enough that Danny DeVito appears in its national commercials, and it has 2,535 locations with plans to open around 350 locations this year — on track for its annual target of 15% unit growth. In January 2020, the average unit volume was $850,000; today, it’s more than $1.3 million. And this year, Jersey Mike’s was No. 3 on Entrepreneur‘s Franchise 500 list.

So, pretty big.

But a love story that skips from infatuation to happy ending is like a sub made only of bread: It’s potentially delicious, and comforting in a fluffy, carb-y kind of way, but it lacks real substance. So what is the rest of the story — the meat and veggies of it? How did a local deli, in what Cancro says was an undeniably poor location (“No parking. You don’t see the sign. You go by it and never see it.”) become one of America’s most successful food franchises?

The answer is, you find a way to scale that mom-and-pop mentality — to stay small, even when you’re getting huge.

Grooming by Kayla Jo Berley at Art Department using Tarte Cosmetics

Image Credit: Bobby Fisher

More then a decade went by before Jersey Mike’s expanded. For years, while Cancro prepared subs, customers told him they were taking the sandwiches back home — sometimes across the country, sometimes across the Atlantic, even into the Soviet Union. Then, in 1987, some of those customers started taking the brand home with them too, by becoming some of his first franchisees.

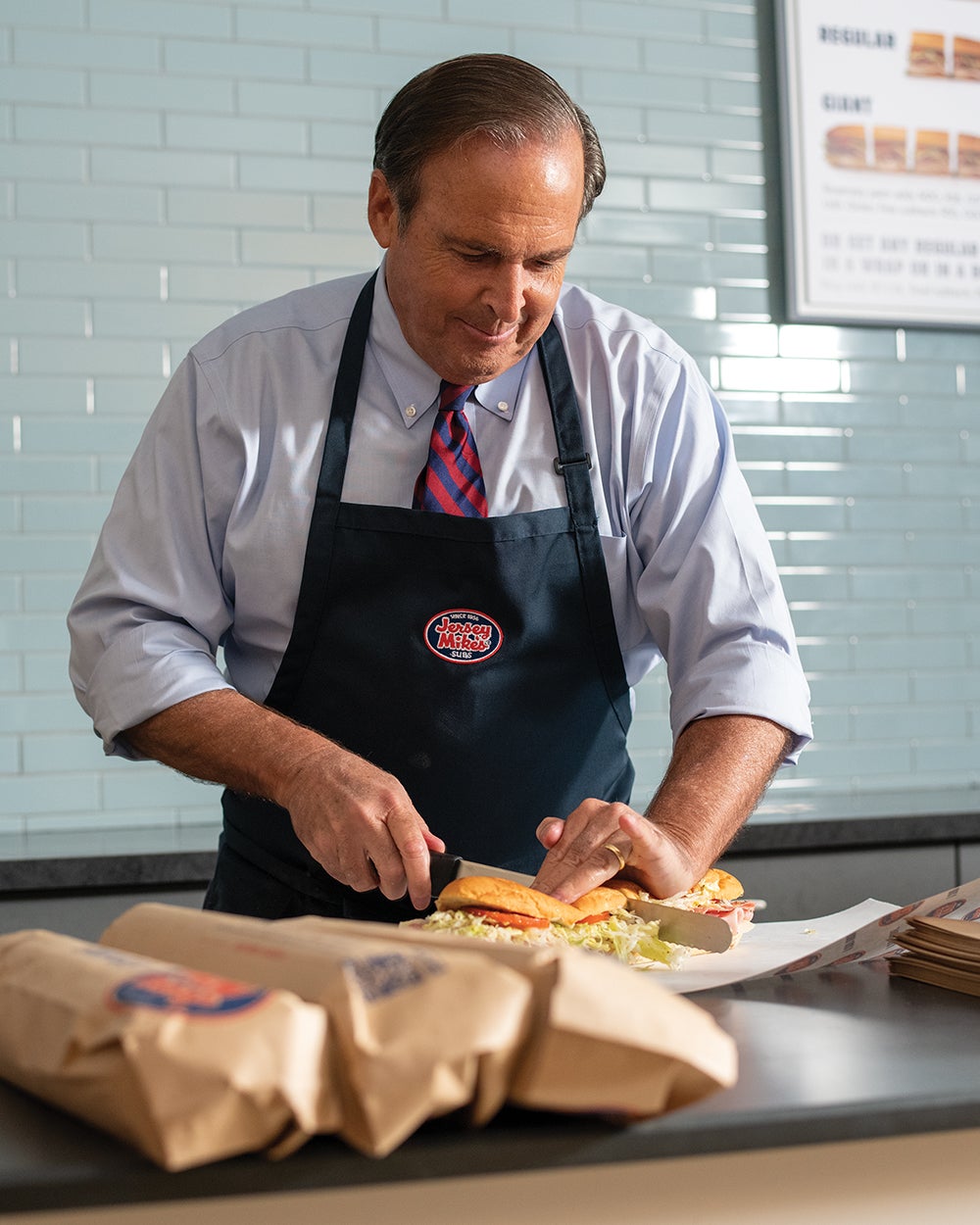

Cancro and his crew were hands-on with the newcomers, teaching everything they’d learned from the original store. “I’d be behind the slicer,” Cancro says. They’d also cook up excitement by going door to door around the community to offer free subs, or by supporting local community organizations. Then, when the store would get hectic, Cancro would become a coach. “I’d take the franchisee: ‘Alright, listen, go over here during the rush,'” he says.

Charitable giving was an important part of Cancro’s vision from the start. Growing up in Point Pleasant Beach, he’d been impressed by two men who respectively owned an ice cream store and a local lobster shanty in the area. “They gave unconditionally to the youth, to the first aid, to the community,” Cancro recalls. “Watching that in high school, I said, ‘Well, that’s what we’re gonna do.’ So we started our mission statement to give and make a difference. ‘The power of the sub sandwich,’ we called it. People know us for that now, as much as they know the product. They say, ‘We hear what you’re doing for the kids. We hear what you’re doing for the community.'”

It’s that same ability to build communities within Jersey Mike’s that Cancro credits for the company’s success. To grow beyond a single mom-and-pop store, Cancro believes in building what he calls a “nucleus.” This is the “stay small while getting large” insight at the heart of his company’s growth. The nucleus, to him, is a small collection of shops in the same area, which work together to build training teams and master multi-unit operations. At first, this will likely develop near the original location, but later, new regions can develop their own nuclei.

Related: 6 Tips to Drive Sustainable Business Growth

Why is this useful? Because this way, no one Jersey Mike’s location feels like a tiny part of a giant system. Instead, each store has a nearby community of support. In addition to ongoing help from the corporate training team, it’s comforting for a mom-and-pop to know there are a couple seasoned franchise aunt-and-uncles and grandma-and-grandpas down the road.

And even once a franchisee is well-established, the franchisor should still be there to help them grow. For instance, whether a franchisee is opening their first location or their fifth, it’s essential to take leasing and site selection seriously. To this day, Jersey Mike’s helps franchisees pick locations, starting with their basic criteria: “You’ve got to see it. You’ve got to be able to get to it. You have to be able to park,” Cancro explains. (Which is to say, it should be nothing like the original Jersey Mike’s.) But on top of that, before signing a lease, you need to know every single potential expense, down to, say, the HVAC or the grease trap. “You include everything, because if you don’t, you’ll be $30,000 short,” he says. “You’ve got to be truthful in your numbers.” Only then can you “open to win,” as Cancro puts it — meaning, open for the least amount of money and with everything turnkey. Otherwise, oversights and surprises can submarine your sub shop.

Then comes the rest: The franchisor develops a training manual, divided into modules, that explains every detail learned from years of mom-and-pop operation — including specifics like how long it should take to slice something. And then, of course, managing other owners is a whole new skill set for a franchisor to master. “What are you going to do when the franchisee says, ‘No — I’m doing it this way’?” Cancro says. It’s no longer just the owner’s business. “If you have a problem, you gotta go in and work with the people and come up with: What do we need to do? Are they doing everything correctly?” By leading multiple shops, franchisors learn to apply their knowledge to new challenges. “You’ve got to be able to turn it around.”

By the end of the ’80s, Jersey Mike’s had about 30 shops — no longer just in New Jersey but also in Tennessee and Ohio and beyond, each region building its own nuclei along the way. “It really started happening,” Cancro recalls. “We hit really well.”

Then the world outside the Mike’s community brought trouble.

Image Credit: Bobby Fisher

As the ’90s began, Jersey Mike’s was all-in on expansion. “Everything we made was going into paying our people and into marketing, and just trying to create our business,” he remembers. “We spent everything we had, plus, plus.” But then, banks began to fail. A recession began. “When the banks fell, and no new stores were coming, we were like, ‘Uh-oh. Where’s our capital? Where’s our money coming from?’ We didn’t have a small business equity line of credit or anything to draw on.”

Even though the existing shops continued to succeed, they couldn’t grow — and Cancro could no longer afford his staff of six at company headquarters. He had to lay them all off. “I was there alone, above one store,” he remembers. “You find out how many bills you can pay when you don’t have any payroll.”

Related: 10 Growth Strategies Every Business Owner Should Know

To Cancro, this underscored the importance of having a financial support system. When aspiring franchisors ask him for advice today — especially if they’re in the food business — he now tells them: “Go to some of the restaurant shows and find out about who is offering capital to restaurants or to fast-casual or quick-serve. Most banks will say, ‘Get away from me.’ But there are lenders out there that charge a few more points and will do restaurants.” Though there’s still value, of course, in trying to work with a local bank when you’re starting out: “They know you. They know your brand.”

Even as franchisors grow, they still need to keep in mind that it won’t only be their franchisees taking on the expenses of each new franchise. “You can’t just franchise and hope it does well,” he says. “It’s a people expense for the training, nurturing, mentoring, coaching, opening the store, ongoing training and assistance, ongoing site visits. That all costs a lot of money for the franchisor.”

To succeed requires a community.

Jersey Mike’s avoided bankruptcy and survived the recession. Within a year and a half, Cancro was able to rehire his headquarters team. As bank failures make headlines today and talk of another recession looms, though, Cancro admits he’s unsure what lessons to take from his experience. “I wish I had capital lined up for ’91 and didn’t spend all my money, thinking that it was just going to keep coming in,” he says. That said, he doesn’t exactly regret spending all his money on expansion either. “It helped our growth. So would I do it over again? Yes.”

Image Credit: Bobby Fisher

Jersey Mike’s growth happened fast. It hit 100 units within its first 10 years. “We were too busy to even stop and congratulate ourselves,” he says. When he doubled that, Cancro recalls talking with Truett Cathy, the late founder of Chick-fil-A, who told him, Peter, you’re at 200 stores. There’s no stopping you now.

But there certainly were things that could slow them down. By that point, Jersey Mike’s had a formula for expansion, and most of the time it worked. Since they first started franchising (and even to this day), when arriving in a new region, the company tends to target suburban areas with a higher-educated, middle-plus-income population. (“Our product is not cheap,” Cancro notes.) This made sense in a stable economy, but it set the brand up for some bumps — like in the early aughts, when the tech bubble burst. This deeply hurt local economies that Jersey Mike’s had bet big on, such as the Research Triangle in North Carolina. “That was another tough time for us,” Cancro says. “But we slowly came out of it.”

Related: Why Franchising May Be the Low-Risk, High-Reward Investment You’re Looking For

The brand continued to grow, and the more it did, the more customers in new regions seemed hungry for its arrival. Still, there is no numerical critical mass that makes a franchise infallible. The way Cancro sees it, the bigger you are, the more you need to be able to rely on the team you’re building. “When you get up to 100 or 200 stores, you’ve got enough capital and enough people, and you really figure things out,” Cancro says. “Hopefully you have the right people coming in. The franchisees, the owners — they help you grow.”

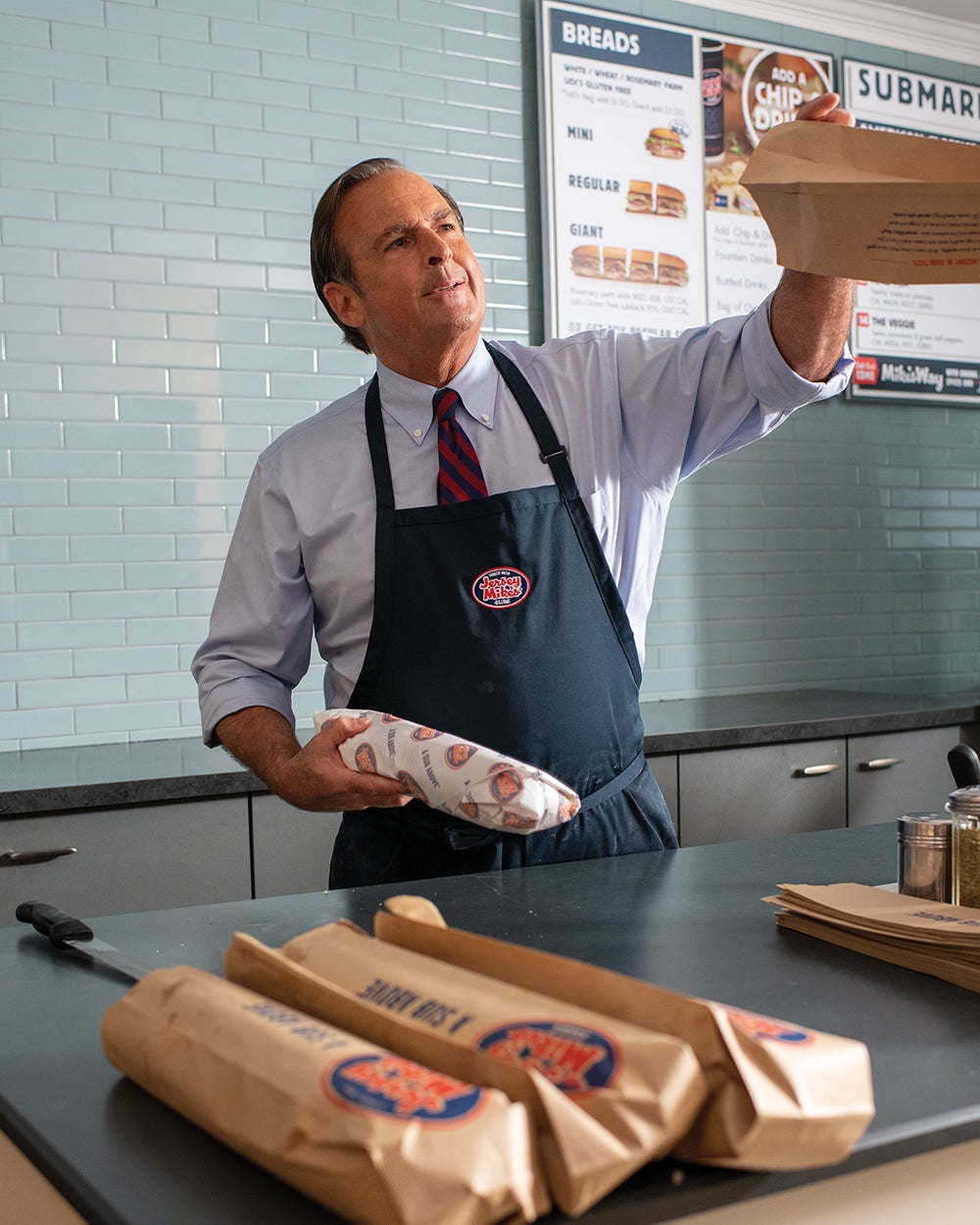

Jersey Mike’s team is still full of zealous trainers (and Cancro himself will take any chance he can to hop behind a slicer). “A lot of chains out there are, like, five, 10 days training,” says Cancro. “Ours is 2.5 months [and] three people to open up a Jersey Mike’s.” The staff makes the subs in real time — “it’s not like a burger where the buzzer goes off and you flip it” — so the new owners have a learning curve. It still takes at least a month to get on the slicer.

In owners, managers, and younger staff, Cancro and his team seek — as much as anything — energy: “The pace, the speed, the sense of urgency.” The training enables them to work swiftly from opening day, encouraged by the two-week presence of at least two Jersey Mike’s corporate staffers overseeing operations and lending a hand. “We do not leave until they’re really good.”

This, too, comes out of that “nucleus” way of thinking — that no Jersey Mike’s location should feel like it’s out there on its own. It’s always part of something that feels small.

On top of the support they get from corporate, Jersey Mike’s owners around the country have taken it upon themselves to build training facilities for their staffs to learn in. “And then at the training stores, you have managers, assistant managers — they become your army ambassadors to be able to help open the stores,” Cancro says. And just how committed to training is this company? Well, that original Jersey Mike’s location is still standing — and still in the original location, with no parking and little visibility. But it’s no longer open for business. Now it’s a training facility for franchisees and their managers and assistant managers.

Image Credit: Bobby Fisher

Today, 48 years on, Peter Cancro is older but still in love, sitting in the conference room of that training facility — though this half of the space wasn’t part of the original shop, but an adjoining hairdresser’s. Next door, on the other side, there’s a pizza-and-subs spot that local high schoolers stop by during their lunch period, revving their engines and honking and joking. Several of Cancro’s own high school colleague buddies from the original Mike’s went off and became teachers or state troopers. “You know what happens the first month after they retire?” asks Cancro. “They get a check. I retire, I get nothing.” Of course, life is easier now. “I don’t drive to Pittsburgh and Columbus, Ohio, to Nashville, to Atlanta and home. I fly. I stay in better hotels,” he says, with a laugh.

Related: We Crunched 5 Years of Franchise Industry Data. Here Are 4 Big Trends You Should Know About.

But there’s still business to be done. In March, Jersey Mike’s raised $21 million for local charities, which included one full day of sales on the company’s annual Day of Giving. His owners are looking to open more shops — though in some cases they’ve maxed out the number of Mike’s that their region can reasonably contain. So Cancro is looking into buying a new concept — likely coffee, chicken, or Mexican — that his franchisees can bring to their communities instead. And he keeps in mind the specter of other sandwich franchise collapses — like Quiznos and Blimpie, which both went from thousands of restaurants to just a few hundred. Cancro says he hasn’t studied the reasons for those collapses (analysts tend to chalk them up to issues with capital, company ownership, and poor relations with franchisees), but that doesn’t stop him from using their stories to affirm his success strategy: “Maybe they didn’t pay attention to the details.”

Cancro still has that restless energy he looks for in others. The bigger the company gets, the more people they can feed, the more good they can do, and the more energized Cancro becomes. You can sense it in the questions he’s still asking, driving his lifelong love affair into its next chapter: “What are we doing? How are we serving? How are we raising up together?”

Read the full article here