A white boy named Jack Daniel and a Black enslaved man known as Nearest Green met on a preacher’s farm in 1850s Tennessee, where Green taught Daniel how to distill whiskey. Daniel would rise to American whiskey fame and make Green his master distiller — but the latter’s contributions were left out of the history books for more than a century until a 2016 story exposed the truth and led to the founding of Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey.

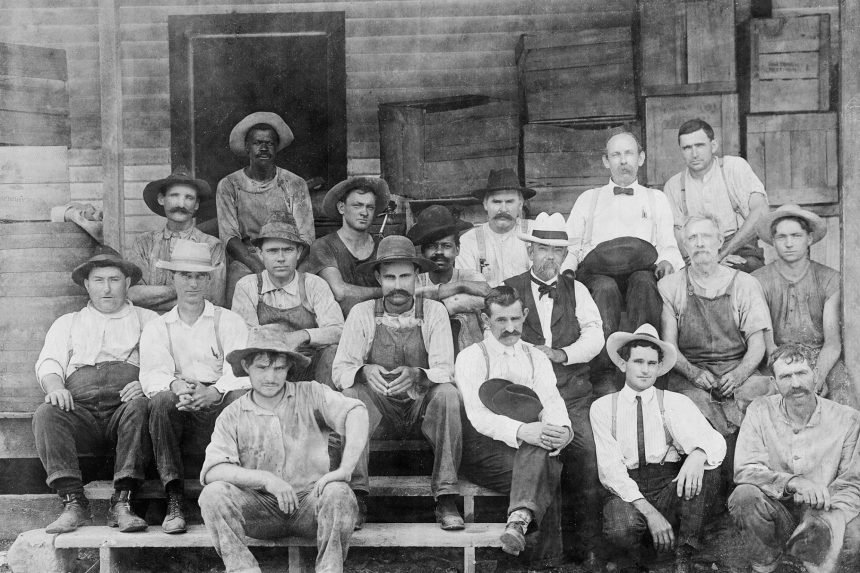

When people hear the tale of a white man and a Black man becoming friends and business partners in the pre-Civil War era, it’s not always “something they believe right away,” says Melvin Keebler, SVP and general manager of Jack Daniel’s Distillery. But “the proof is in the pictures,” he adds.

By and large, people want to hear good stories and see reasons to hope — especially during difficult times.

Such was the case in 2020 when civil unrest erupted across the country in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Amid the tragedy and turmoil, many were moved to take action toward tangible change, including Uncle Nearest Green Inc. and the Brown-Forman Corporation, which partnered on the Nearest & Jack Advancement Initiative to further diversity within the American whiskey industry.

“[It] was the right time at the right moment — [there was] a lot of racial injustice within this country,” Keebler says of the initiative’s origin. “[And] it wasn’t just the idea of getting more diversity in the industry. It was collaboration at a time when people needed to hear good stories.”

Related: Formerly Enslaved Black Man Nearest Green Taught Jack Daniel Everything He Knew About Whiskey

Melvin Keebler

Image Credit: Courtesy of Jack Daniel’s

A Black-owned distillery in Minneapolis is impacted by the 2020 protests

Shortly before the Jack Daniel’s and Uncle Nearest collaboration, the story of Du Nord Social Spirits founder Chris Montana was gaining attention in Minneapolis. When protests rocked Montana’s community, the distillery he and his wife Shanelle opened in 2013 was set ablaze, triggering a fire suppression system that saved the building — but unleashed 26,000 gallons of water upon it in the process.

It was another blow for the distillery, which had shuttered its popular cocktail room that March.

Almost a decade prior, Minnesota’s changed laws around distilling and significantly reduced licensing fees compelled Montana to leave his law career and lean into whiskey — “what beer wants to be when it grows up,” he jokes. But Du Nord needed to release an unaged spirit “to keep the lights on,” so the focus soon expanded to include vodka, then a coffee liqueur and more. Du Nord’s launch was quick, but distribution continued to prove challenging.

As the destruction crept closer to Du Nord in 2020, an employee put up signs indicating it was a Black-owned business, which brought up “complicated” feelings, Montana says. Though Du Nord was Black-owned, that had never been its “calling card” — and that was very intentional.

I had to go through an evolution in how I was thinking [and] talking about being a Black-owned business.

“Growing up in Minnesota, I stood out everywhere all the time,” Montana explains. “And I was always my race in front of anything else I would do. I was a Black kid. I wasn’t a kid. When I became a lawyer, I was a Black lawyer. I wasn’t a lawyer. And it’s not that I have a problem standing out, but I also sometimes want to be known for other things first.”

When Montana launched Du Nord, he liked the fact that the bottle would represent him on the shelf.

“I wanted people to try that product and say, ‘This is great,'” Montana says. “That was going to be the validation — and that alone. I didn’t want anyone to buy our products simply because it was made by a Black person. That won’t affect the quality of what’s in the bottle.”

Montana and his wife received widespread support following the fires in their warehouse, and with an insurance claim pending, they started a GoFundMe to support other small and underrepresented business owners whose physical stores or offices were damaged. A steady stream of donations followed, and the couple decided to channel the funds — more than $1 million — to start the Du Nord Foundation, which addresses racial inequities and builds economic justice in the Twin Cities by providing immediate relief and long-term investments in entrepreneurs and business leaders of color.

“I had to go through an evolution,” Montana says, “in how I was thinking [and] talking about being a Black-owned business, to get to a place where I’m not only comfortable about it, but I’m celebrating it, and I understand where that message sits within both the business community and in what Du Nord is trying to do.”

Related: Her Great-Great-Grandfather Taught Jack Daniel How to Distill Whiskey

Chris Montana

Image Credit: Ken Friberg

Out of the chaos comes the potential to give back — and another opportunity

Montana says Du Nord was running in “emergency mode” as it strove to help its community in those early days.

Not only was Du Nord heading up a food and supplies operation to give necessities to those who couldn’t afford to get out to the suburbs, but it was also working to spread much-needed awareness for other local businesses that hadn’t received the same level of attention and considering the long-term issue of diversity within the business community — “because it’s not an accident that all that anger got played out into a business community,” Montana says.

In the midst of it all, the Nearest & Jack Advancement Initiative was also taking shape.

Keebler of Jack Daniel’s recalls receiving a phone call from whiskey connoisseur Fred Minnick, who wanted to run a benefit for Du Nord. From there, Fawn Weaver, founder and CEO of Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey, got in touch with Keebler and shared a big idea she and former Brown-Forman executive Mark McCallum were working on: developing a major initiative that would promote diversity in the spirits industry.

The initiative would build on one program that was already underway — the Nearest Green School of Distilling, which leverages an accredited STEM-based curriculum at Motlow State Community College with an emphasis on the distilling industry.

The Leadership Acceleration Program, which aims to advance the careers of Black professionals within the spirits industry, and the Business Incubation Program, which bolsters business development for Black entrepreneurs with access to industry expertise and resources, would follow to round out the three-part endeavor.

Keebler says Montana was a “natural fit” to become the first graduate of the Business Incubation Program.

And as overwhelming a time as it was for Du Nord and its community, Montana was more than grateful for the opportunity.

“The thing that struck me then the most, and continues to strike me, is the fact that it happened at all,” Montana says, “that all these resources, all these people, that I now had access to who had an understanding of the industry that is unparalleled, were a phone call away whenever I wanted them to be.”

Related: Why Continuous Learning Is Critical for Entrepreneurs and Their Teams

Good stories and changemakers withstand the test of time

Today, Du Nord continues to distill and distribute its award-winning spirits — counting whiskey, vodka, gin and coffee and apple liqueurs in its repertoire — and even landed a partnership with Delta Airlines in 2021. Through it all, the company continues to do good too, developing its BIPOC Wealth Development & Incubator Project as it determines “where exactly [it] can fit into that ecosystem” of existing nonprofit organizations in the Twin Cities.

Du Nord’s revival and ongoing commitment to its community is one of those good stories people want to hear, capturing how much is possible in turbulent times with determination, collaboration and the desire to give back.

It’s a cyclical tale that’s withstood the test of time too — going back to the unlikely friendship between Daniel and Green, who, despite all societal norms and expectations, forged a partnership based on mutual respect that continues fostering change in the world nearly two centuries later.

Read the full article here